The industry has regained its manufacturing pace, but potential disruptions in chip supply remain, and production momentum disruption has pushed a 100-million-unit year into the next decade.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the availability of semiconductor chips took a drastic toll on all facets of the automotive industry, and in turn the global economy. But in mid-2023, the worst of the fallout seems to have settled, and the auto industry has found a new normal. In short, the dearth of supply of semiconductor chips that hobbled vehicle production for most of 2021 and 2022 has faded into the background — with some exceptions — according to recent analysis by S&P Global Mobility.

S&P Global Mobility estimates that in 2021 more than 9.5 million units of global light-vehicle production was lost as a direct result of a lack of necessary semiconductors, with the third quarter of 2021 experiencing the largest impact with an estimated volume loss of 3.5 million units. Another 3 million units were impacted in 2022. (These losses are estimated from analyzing original equipment manufacturer announcements, compared to S&P Global Mobility’s estimate of production planning volumes during the same timeframes.)

During the first half of 2023, however, losses identifiable as specifically related to the semiconductor shortage fell to about 524,000 units globally. Although the supply of semiconductors remains constrained, more predictable availability has allowed automakers to adapt their production schedules.

As a result, we see semiconductors as a specific cause of production disruptions happening with less frequency.

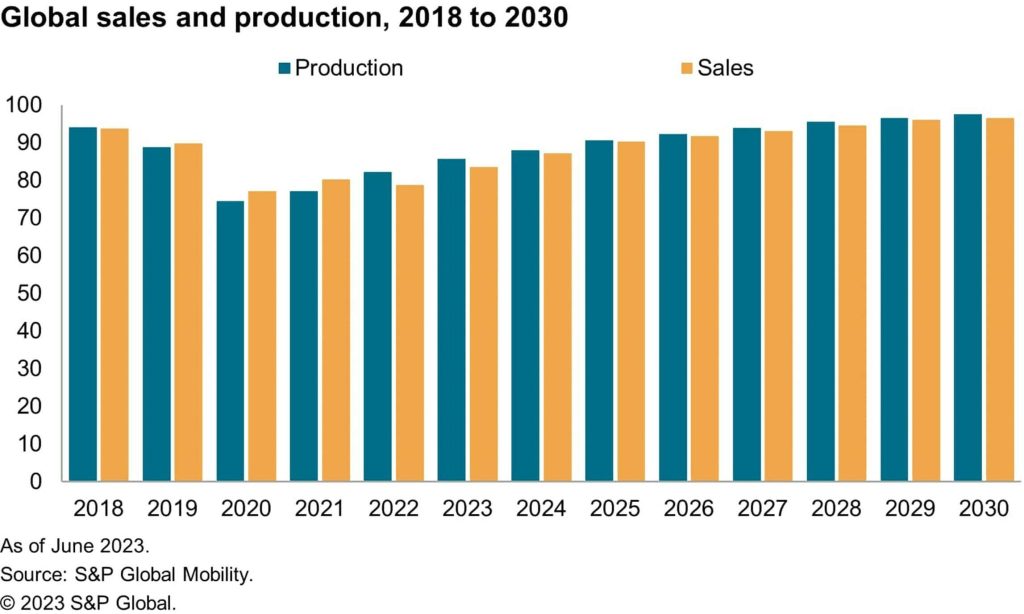

Production in 2023 has improved as automakers and suppliers have adapted to the current environment, and 2023 sales are improving with more inventory. That said, the pre-pandemic momentum toward a 100-million global vehicle production year has been set back by a decade, according to S&P Global Mobility analysis.

So, where are we in mid-2023?

To level-set expectations, prior to the pandemic there always were semiconductor supply chain challenges — but they tended to be episodic, impacting a single component type or individual supplier. The semiconductor suppliers have customer service and production readiness teams working behind the scenes, and these resources have always managed these types of shortages with only rare interruptions in service.

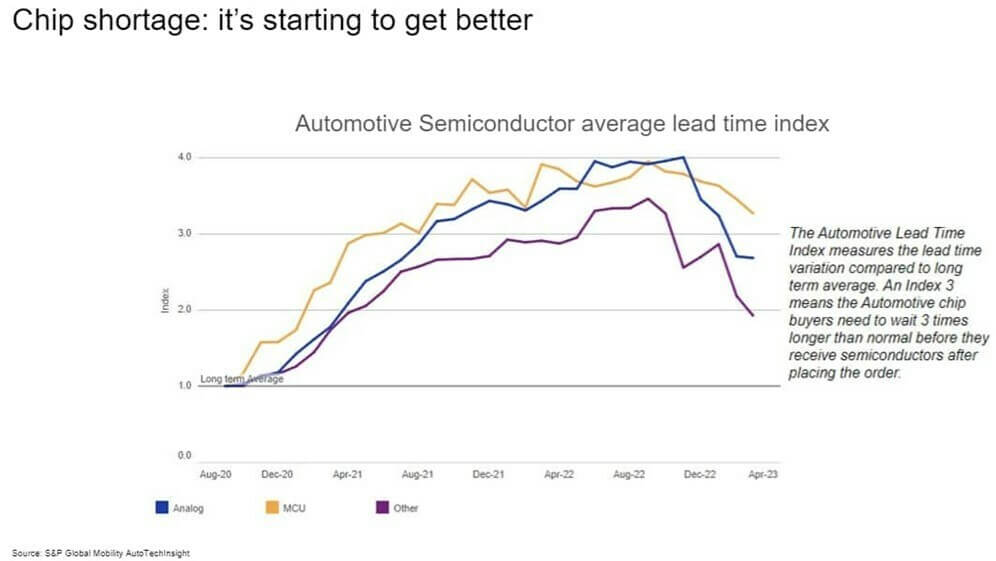

What was unique about the pandemic period was the wholesale shortages among virtually all suppliers, impacting multiple component types (including microcontroller units — or MCUs — and analog based on mature process node capacity).

“We’ve moved from obvious disruption, clearly visible at the automaker and plant level, to a stage where we know constraint remains, but it is impossible to identify,” said Mark Fulthorpe, S&P Global Mobility executive director of global light-vehicle production.

“We are now in a position where the auto industry has adapted to a constrained supply, and as a result is much less likely to be hit by significant disruption,” Fulthorpe added. “With the current semiconductor supply levels, we estimate that 22 million units of global light-vehicle production per quarter could be supported.”

However, industry demand for increasingly complex infotainment, advanced safety and vehicle autonomy systems will continue to escalate usage of semiconductors in vehicles. Phil Amsrud, senior principal analyst in the S&P Global Mobility supplier and components team, estimates that the value of semiconductors installed in vehicles averaged US$500 per car in 2020, but is forecast to reach US$1,400 per car by 2028.

“Before the pandemic, the lead time from order to shipment of chips was three to four months. During the pandemic in 2021 and 2022, that wait grew to a year or longer,” Amsrud said. “But while other industries — such as mobile phones and PCs — have experienced cooling demand of late, automotive semiconductor demand is increasing, and some chip manufacturers have pivoted capacity to address that need.”

That said, the types of chips for automotive-grade use versus communications equipment often are not the same; or there are different qualification levels in automotive that complicate using consumer grade components in automotive applications, Amsrud noted.

Potential for future disruption

Although the semiconductor crisis is largely resolved, the chip supply situation still carries a degree of uncertainty. Demand still exceeds supply of several chip types. There is a shortage, even as the auto industry can better manage it today than two years ago. Pressure on the supply chain remains with risk of further disruption.

While demand for chips from the consumer electronics industry has softened recently, it is likely to rebound while the use of semiconductors in autos continues to increase, which are factors indicating continued pressure. Meanwhile, the structural lack of capacity for mature node capacity has not been addressed. Geopolitical trade risks remain as well, as evidenced by mainland China’s decision in early July to restrict exports of some key semiconductor materials. Trade tensions between the US and mainland China remain high, and the semiconductor supply can still be affected by future moves from either side.

Consolidation of electronics in cars is also driving the automotive semiconductor demand, with domain controllers and central computers replacing electronics control units (ECUs). This does not lessen the need for chips, but rather means more — and more powerful — chips are needed.

The good news is this consolidation enables the use of more advanced system-on-chip (SoC) and discrete memory, which are processed at more advanced process nodes. This is where most capacity investment is going. The bad news is some analog, discrete and power components will always be on mature process nodes, which receive much less investment. The movement to domain controllers and central computers may reduce the number of modules per vehicle and will change the mix of semiconductors but it will not reduce the overall number of semiconductors. Analog, discrete and power devices will get little if any benefit from moving to advanced process nodes.

There also is the question of how OEMs approach the manufacturing capacity equation, following two years of lower volumes but — in some cases — stronger profits. Faced with lower capacity, largely due to the chip crisis, automakers were able to command higher pricing, heavily reduce reliance on incentives, and allocate chips to higher-margin products and trim levels within product lines.

For those automakers, there may be a rethink on how to manage the inventory versus demand, and incentive to support the pricing power with managed production and to continue allocating chips to high-margin, high-feature set vehicles that inherently also require more chips. Looking forward, the question may not simply be how many chips are available to the automotive industry, but how different automakers allocate their supply.

Industry trajectory set back by a decade

While production and sales are improving, and semiconductor supply is no longer expected to be a source of disruption for vehicle production, there is little chance to “make up” the lost production or sales from 2020 through 2022. The early-2019 S&P Global Mobility forecast — issued prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent shutdowns — expected both global sales and production to exceed 100 million units annually as soon as 2022.

That milestone is now not expected until past 2030, according to our analysis, demonstrating that the auto industry’s growth trajectory has been thrown off by roughly a decade compared with pre-pandemic expectations. The semiconductor crisis was among the most disruptive of several external impacts that combined to drive down the opportunities expected in 2019, but certainly not the only one.

Global light-vehicle sales reached 93.8 million units in 2018. Several factors caused sales to drop in 2019, and then COVID-19 and associated impacts led to a 14% year-over-year decline in global auto sales in 2020. The recovery in 2021 was held down by production constraints rather than by a lack of consumer demand or willingness to buy, and in 2022, those constraints caused yet another decline.

The June 2023 S&P Global Mobility forecast sees sales reaching 83.6 million units globally this year — another 93-million-unit year is not forecast until 2027, thus pushing the potential for sales above 100 million units past 2030.

As for global light-vehicle production, that number reached 94.1 million units in 2018, also falling in 2019 to about 88 million. The pandemic and related supply chain woes pulled production down by 16% year over year in 2020. With supply chain issues approaching a more normalized situation in 2023, output is forecast to reach 85.6 million units this year. Although we will see another 88-million-unit production year in 2024, output above 94 million units is not expected to occur until 2028.

Mid-2023 marks an inflection point when the semiconductor supply is no longer limiting vehicle production. There will continue to be parts of the supply chain that pose threats but those seem more episodic than systemic. Geopolitical threats persist in terms of wafer and packaging capacity in the Asia-Pacific region, but the industry is also moving forward with adding capacity in Japan, Europe, and North America.

The effectiveness of and responses to the US-led semiconductor technology embargo are still to be determined. Rebounds in non-automotive semiconductor market growth are an unknown factor. From the automotive industry perspective, lessons learned from the pandemic shortages — especially the long-term balance of mature versus advanced process nodes — is critical.

The trends of electrification and autonomous driving will impact vehicle architectures, which in turn will impact the mix and number of semiconductors used. The industry may have survived the COVID semiconductor crisis, but that does not mean it is out of the woods.